Essentials of Japanese Language

Lesson Key Points

- As a first step in learning Japanese, we will explore the unique characteristics of the language. This section provides a brief overview, while more detailed explanations will follow in subsequent lectures.

- As a first step in learning Japanese, we will explore the unique characteristics of the language. This section provides a brief overview, while more detailed explanations will follow in subsequent lectures.

Writing system

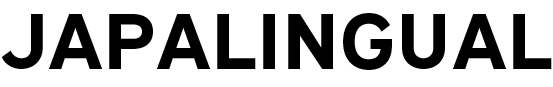

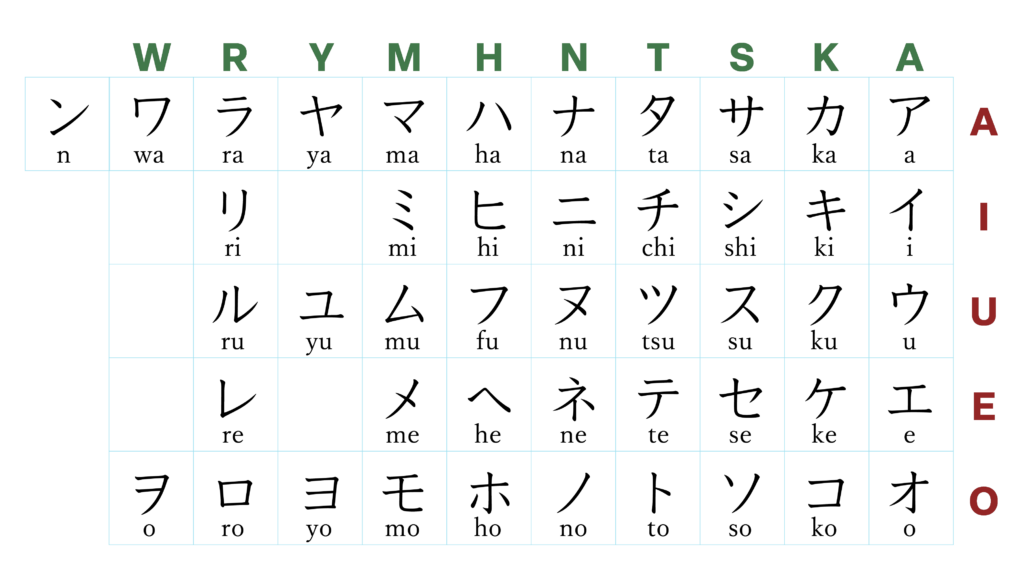

The Japanese writing system is characterized by its complexity and flexibility compared to other languages. The main types of characters used in Japanese are hiragana, katakana, and kanji.

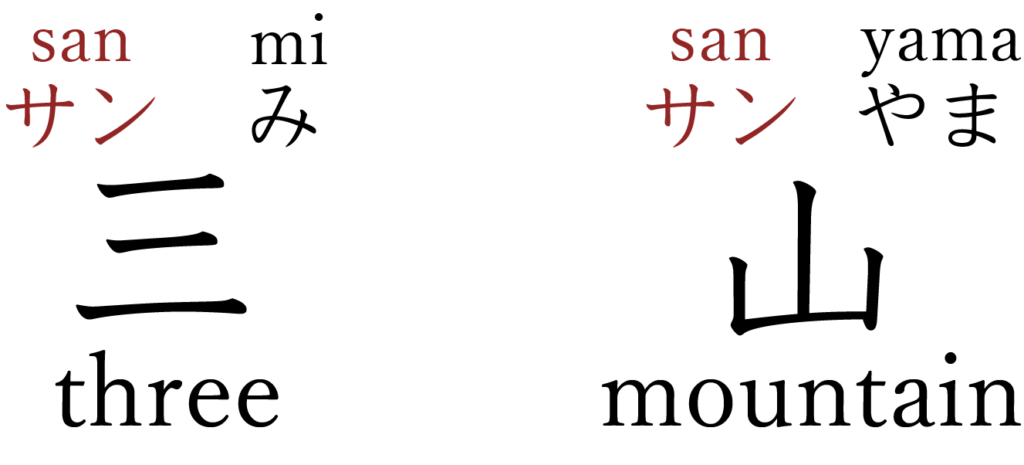

The writing system can be divided into two main categories: phonograms, which represent sounds, and logograms, which represent meanings. Kanji, as well as ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, are examples of logograms. Each logogram represents one or more meanings and may have multiple pronunciations. Phonograms, on the other hand, can be further divided into two types. The first type is phonemic characters, which use phonemes, the smallest recognizable units of sound, as their building blocks. The alphabet used in English is an example of phonemic characters. The second type is syllabic characters, which use syllables—units of sound that typically include at least one consonant and one vowel. In Japanese, hiragana and katakana are syllabic characters.

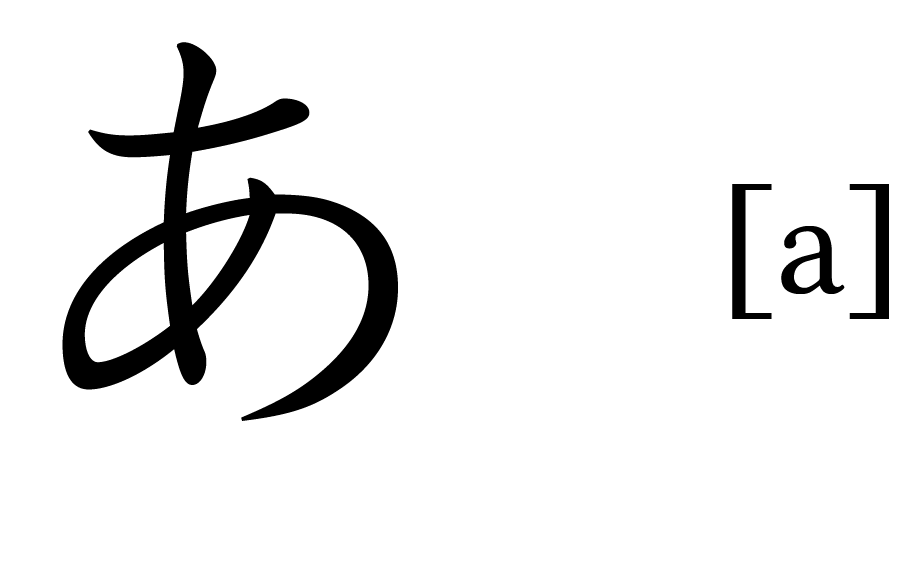

Hiragana

This table only shows the voiceless sounds in Japanese. Other voiced sounds are represented by adding diacritical marks to these hiragana.

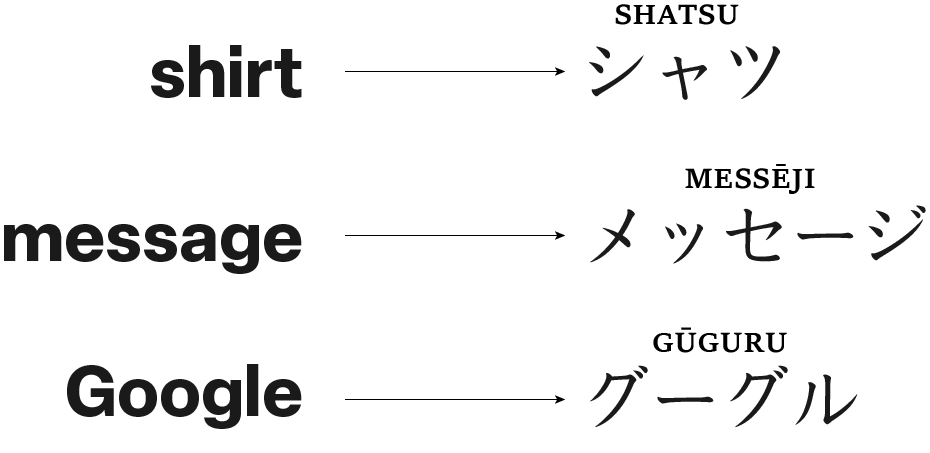

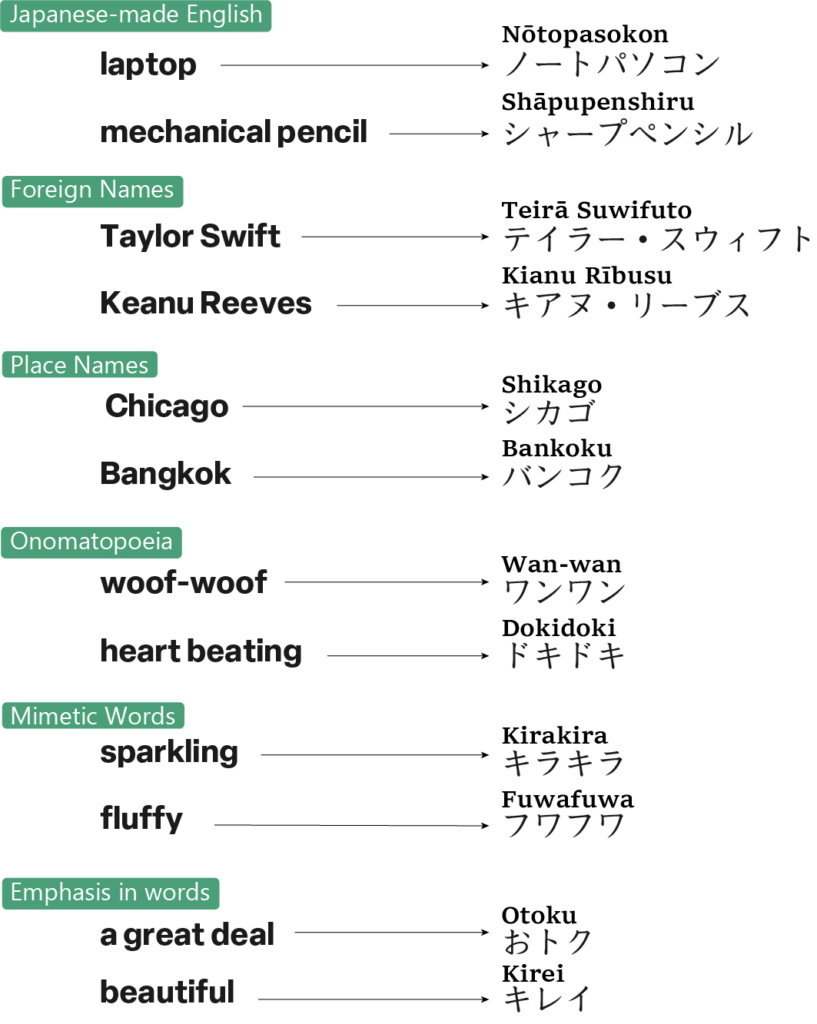

Katakana

Additionally, katakana is used in various contexts. Primarily, it is employed for wasei-eigo, or Japanese-made English expressions, as well as for foreign names and place names. Katakana is also commonly seen in onomatopoeia and mimetic words, which convey sounds and descriptive imagery. Furthermore, katakana can be used for emphasis, particularly when highlighting specific words or phrases.

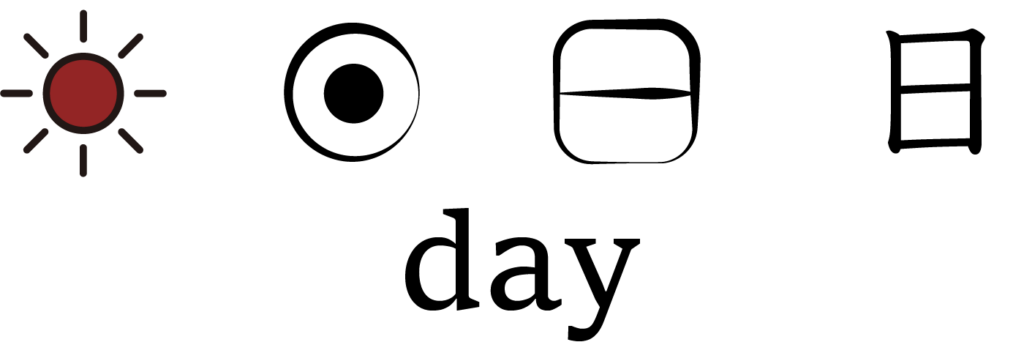

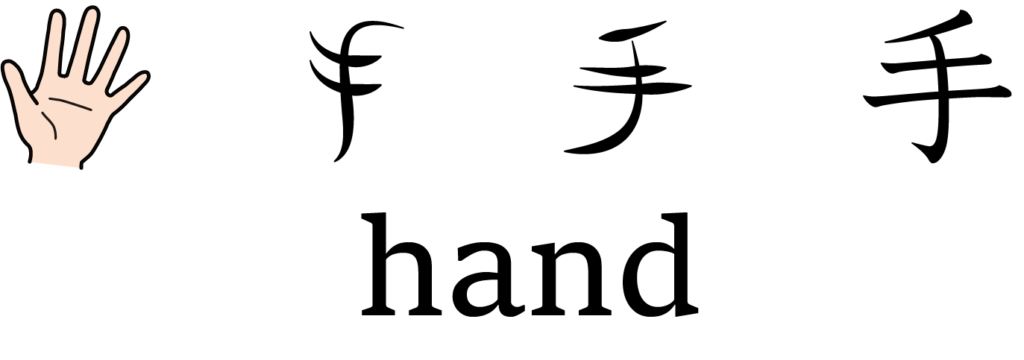

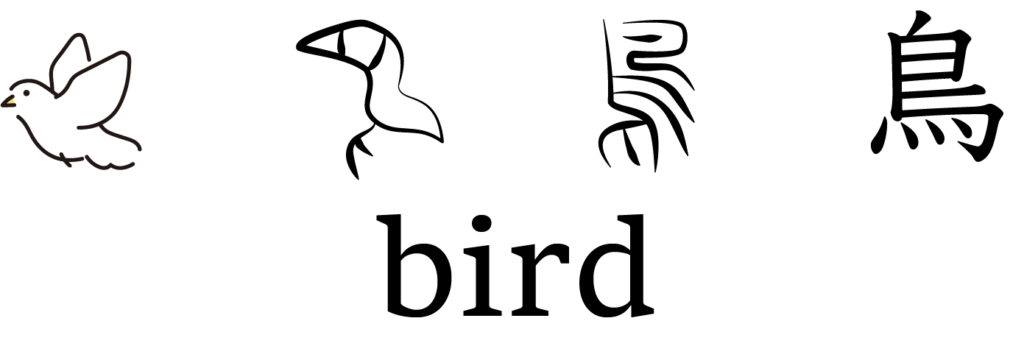

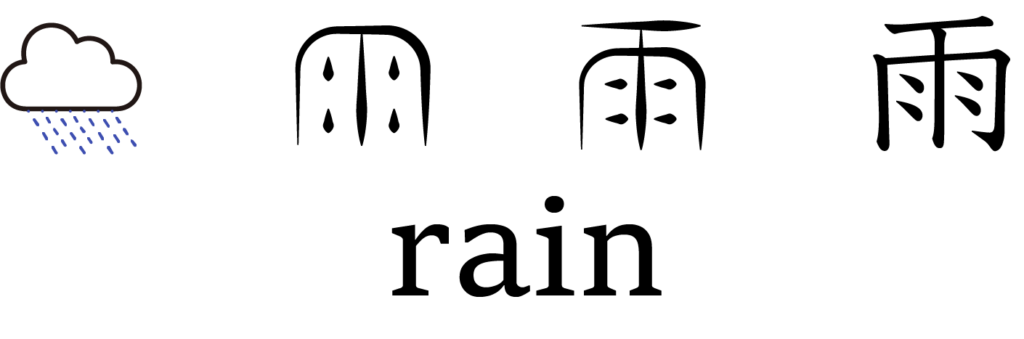

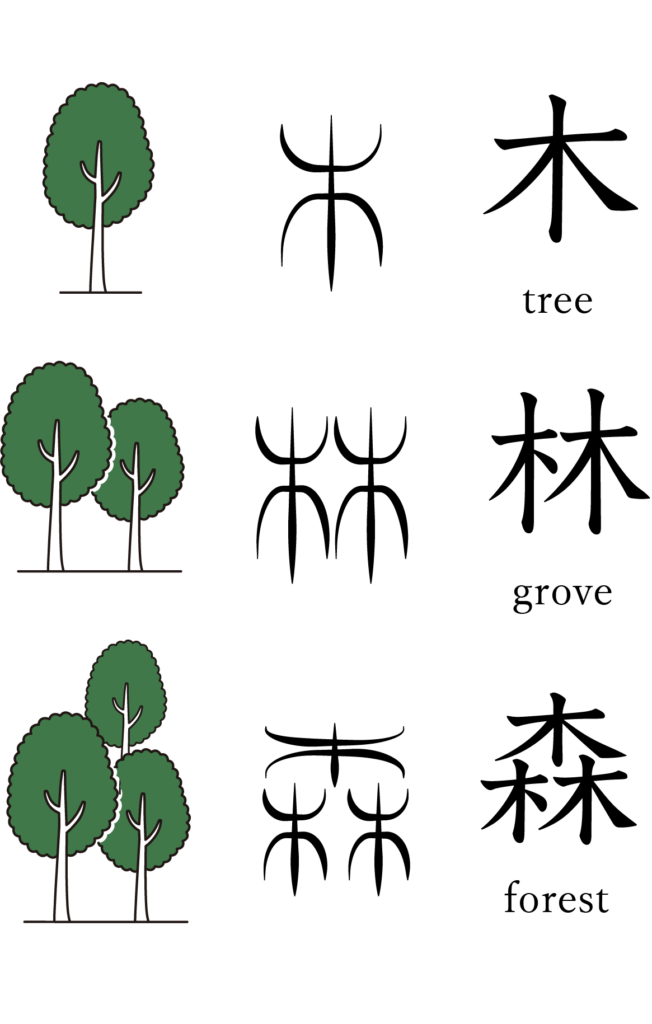

Kanji

Understanding the origins and structure of each kanji, including why a particular kanji has a specific radical or shape, can enhance your comprehension and retention when studying kanji.

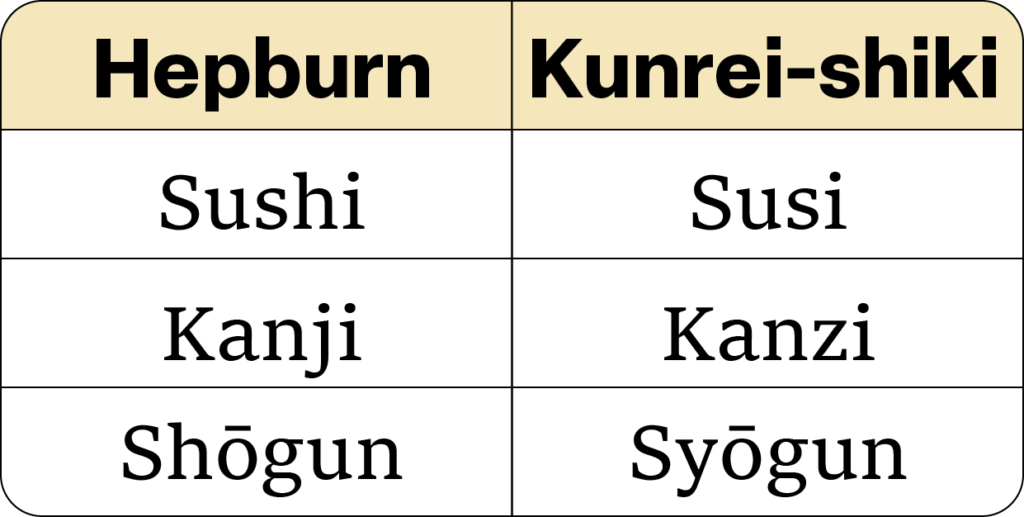

Romanization and Numerals

On this site, we use the Hepburn system for romaji, with long vowels indicated by macrons.

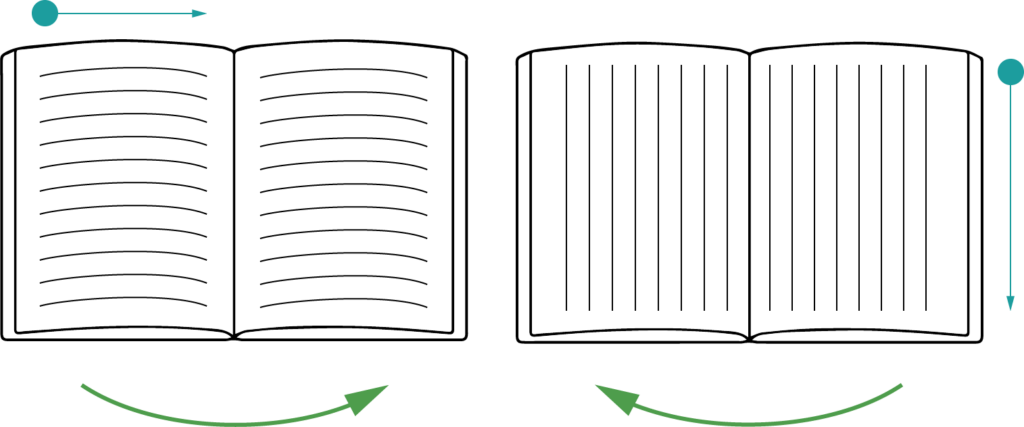

Vertical and Horizontal Writing

Japanese can be written in both vertical and horizontal formats. Traditionally, text is written in a vertical format, moving from top to bottom and progressing from right to left across the page. Vertical writing is commonly found in literary works such as novels, poetry, and plays, as well as in newspapers. In manga, speech bubbles are usually written vertically.

In contrast, horizontal writing became more prevalent after the modernization period to align with Western cultural practices. This format is primarily used in specialized books on subjects such as foreign languages, mathematics, science, and music. Documents that contain horizontally written text, mathematical formulas, or musical scores are typically arranged horizontally. Furthermore, web pages, TV, DVD subtitles, and other visual media also employ horizontal writing.

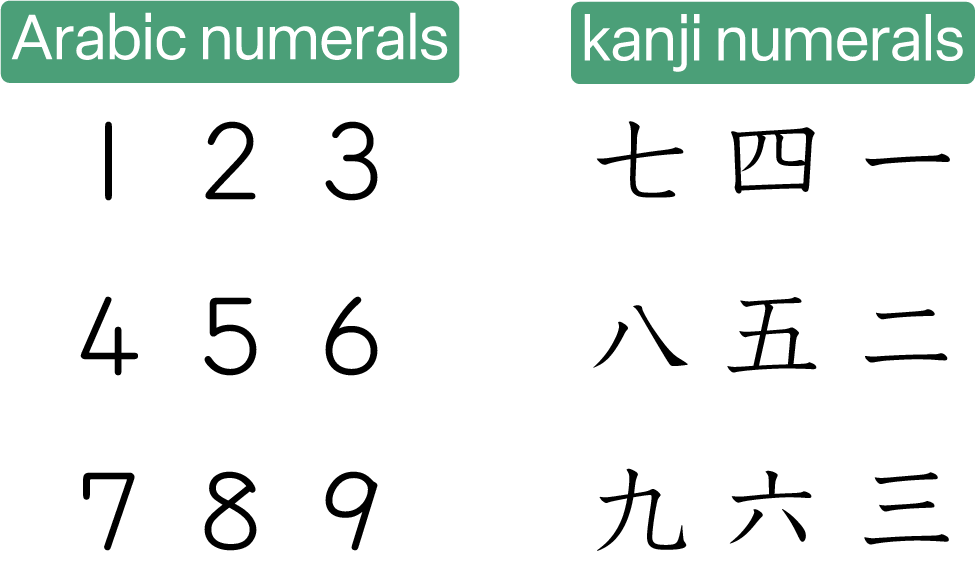

In Japan, both Arabic numerals and kanji numerals are used for representing numbers. As a general rule, kanji numerals are used in vertical writing, while Arabic numerals are used in horizontal writing. Arabic numerals are often used when indicating quantities or orders, especially when other numbers can be substituted, like page numbers or dates. On the other hand, kanji numerals are commonly used for idiomatic expressions and fixed phrases.

Grammar

SOV

Subject and Predicate

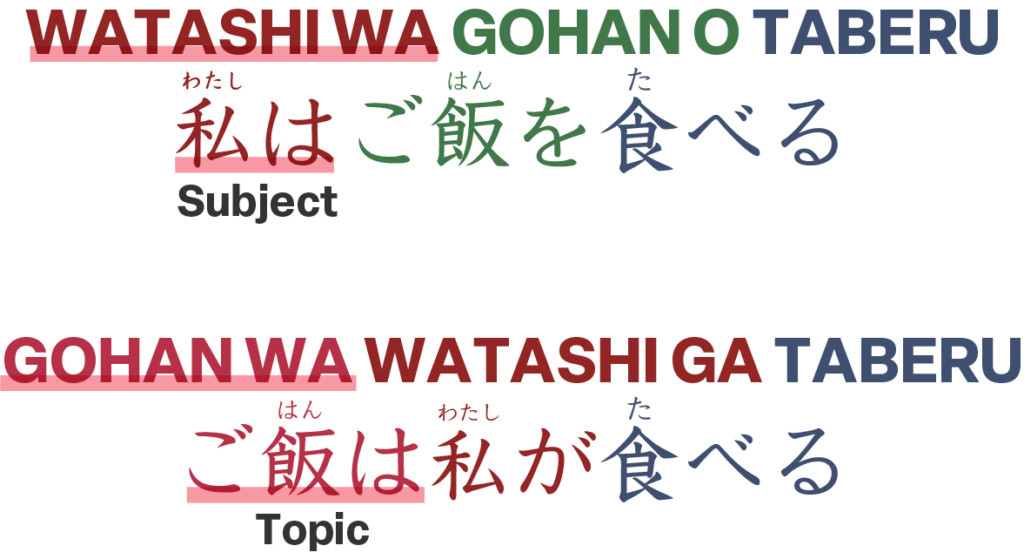

Thus, in Japanese sentence structure, the word that appears at the beginning of a sentence is not necessarily the subject of the verb, but rather the topic of the conversation. This feature highlights the importance of the topic in determining the focus and content of the sentence.

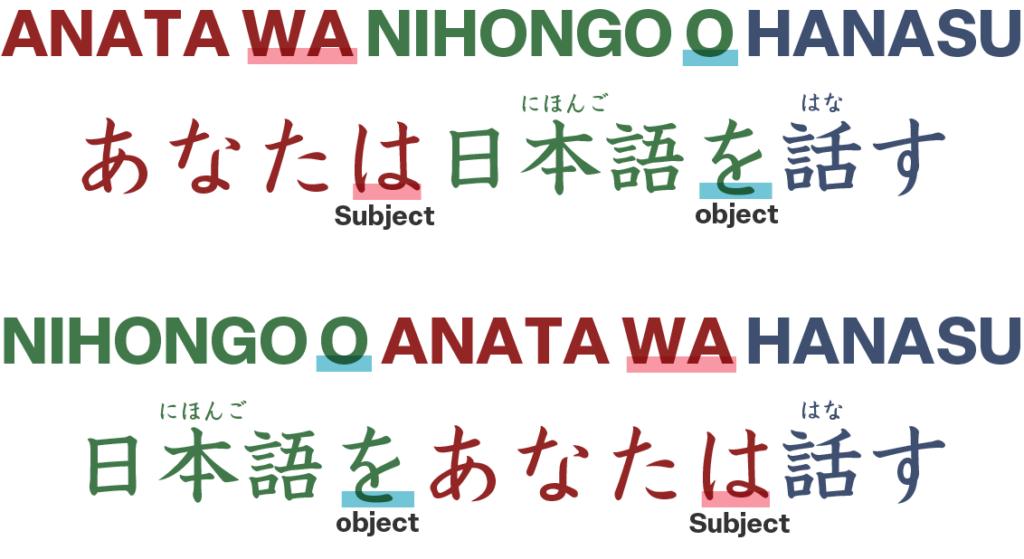

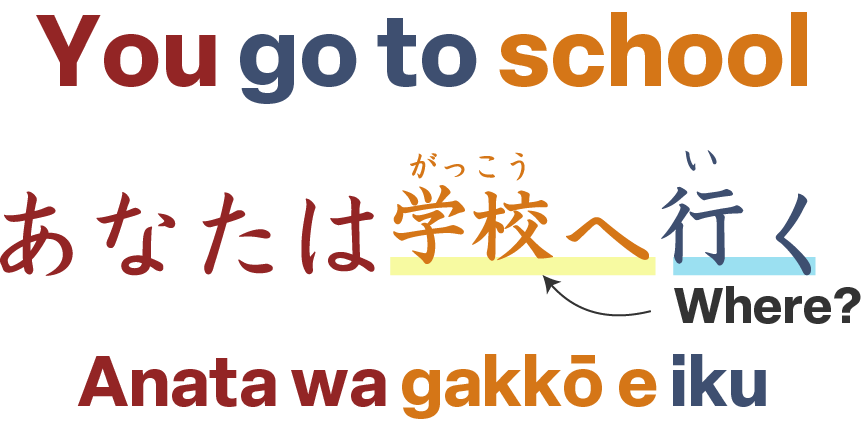

Particles

Modifiers

Omission

In Japanese, there is a tendency to omit information that can be inferred from context. Subjects and possessives are often left out when they are not necessary to be explicitly stated. Additionally, information that is already known to both parties is often omitted in conversation.

One reason why Japanese is considered difficult is because of Japan’s high-context culture. In Japan, communication often relies less on words and more on understanding the context or reading “between the lines” to grasp the speaker’s intent. As a result, conversations can often proceed without explicitly stating everything.

honorific

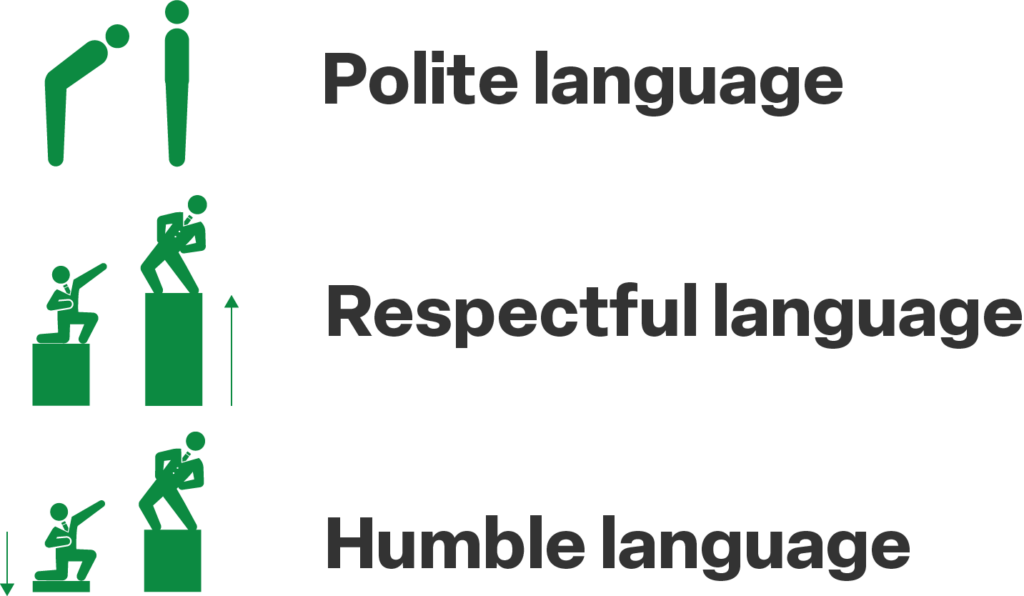

Honorific language in Japanese reflects the relationship between the speaker and the listener. It is used to facilitate smooth communication, build good relationships, and express respect or a formal attitude. There are several types of honorifics in Japanese, with the main categories being polite language, respectful language, and humble language.

Polite language (teineigo) is used in everyday situations with anyone and conveys politeness toward the listener. Respectful language (sonkeigo) is used to show respect toward someone of higher status or someone unfamiliar, elevating the status of the person being spoken about. Humble language (kenjōgo), on the other hand, is used to lower oneself to show respect and elevate the status of the listener or the person being spoken to.

It is important to use honorifics correctly, as using humble language when the subject is a superior could cause offense or create a negative impression. This is especially important in business settings, where a mistake in using honorifics could lead to embarrassment. Therefore, it is essential to gradually learn the proper use of honorific language.